Olga Belova: Mr Lavrov, thank you so much for agreeing to this interview today. Thank you for your time. We are recording this interview on the eve of the second round of Ukraine’s presidential election, so if you would allow me, we will begin with this subject, since it is currently making headlines. Against this backdrop we cannot fail but to recall the events that took place five years ago during the 2014 election in Ukraine. Since then the question of whether Russia had to recognise the outcome of the 2014 election resurfaces from time to time in the public space. What will happen this time around? Does recognising this election make any sense? We understand all too well that Russia has many formal and moral reasons to break up all contacts with the Ukrainian authorities.

Sergey Lavrov: Five years ago when the presidential election was called in Ukraine, it happened in the aftermath of an armed and anti-constitutional government coup that, for some reason, was carried out within a day after the signing of an agreement between the opposition and President Viktor Yanukovich. Moreover, foreign ministers of Germany, Poland and France assumed the role of guarantors under this agreement that was also proactively backed by the US. But the next morning the opposition announced on Maidan Square that they had seized power and had formed a government of victors. This is when they began splitting their people apart. This agreement was signed on February 21, 2014, and if we recall its text, the first paragraph sets forth the need to form a “national unity government.” Instead, they established a government of victors, and started treating everyone else like losers. They put forward multiple requirements that ran counter to the interests of a significant part of people in Ukraine, including minorities such as Russians and Russian speakers. All this brought about serious problems and triggered a referendum in Crimea as a response to the threats made by nationalists to expel Russians from the peninsula and attempts to take over the Supreme Council building by force.

Let me mention one more event. In mid-April, that is before the election was called, but after the referendum in Crimea, Geneva hosted a meeting attended by US Secretary of State John Kerry, yours truly, EU High Commissioner for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Catherine Ashton, and then acting Foreign Minister of Ukraine Andrey Deshitsa. At this meeting we agreed on a one-page declaration, and its key provision consisted of supporting the intention of the Ukrainian authorities to implement federalisation, that is to decentralise the country with the involvement of all regions. A representative of the new Ukrainian government that came to power in Kiev following a coup signed this document, guaranteeing federalisation with the involvement of all regions of the country.

But this commitment was instantly forgotten. Against this backdrop, when people started to state their intention to run for president, President of Ukraine Petr Poroshenko was saying on every street corner that he was a “president of peace” and would settle the conflict in a matter of two or three weeks. It is for this reason that Western capitals, Paris and Berlin, urged Russia to refrain from making a statement rejecting the election outcome. We did refrain in order to give them a chance.

In early June 2014, President-elect Petr Poroshenko met with President of France Francois Hollande, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and President of Russia Vladimir Putin, when they all attended celebrations of the allied Normandy landings. The very fact that Vladimir Putin took part in this meeting, proposed by France and Germany, attested to Russia’s commitment to peace in Donbass and protecting the rights of those who were firm in their refusal to accept an armed coup. We proceeded from the premise that Petro Poroshenko was primarily elected for this promise to resolve the problem peacefully. With this in mind, I would refrain from stirring up the past on this particular matter.

By the way, during the Normandy format meetings that followed, Petr Poroshenko proved that he was not a “president of the peace,” and was forced by the developments on the ground to sign the Minsk Agreements. Russia also believed that it was unacceptable for him to consistently fool his people, while also lying to his curators abroad, since they were irritated by Poroshenko “getting out of hand.” I am talking about the Europeans represented within the Normandy Format, namely France and Germany. When the Minsk Agreements were signed everyone let out a sigh of relief, considering that this created a clear path to peace, especially since the UN Security Council approved the Minsk Agreements, thus implementing them into international law. However, in this sphere as well Petr Poroshenko proved to be very apt in dodging responsibility, turning for protection to the US administration which does not encourage Ukraine to abide by the Minsk Agreements. The Europeans found themselves in an awkward situation.

This was a look at the past, but coming back to your question, we have seen electoral programmes released by Petr Poroshenko and Vladimir Zelensky. We see how they approached the run-off. I have the impression that what matters the most for them at this point is to attract voters by some kind of a constructive agenda in order to secure victory. This is what their efforts are all about. I would rather not draw any final conclusions on what Vladimir Zelensky’s policy will look like if he is elected president, which is a done deal as far as observers are concerned. I would refrain from paying too much attention to declarations coming from his campaign. We have to wait for the second round results when they will have to deal with real things instead of campaign slogans and propaganda. Only then will we understand what this person as president thinks about the millions of his compatriots who speak Russian, love the Russian language and culture and want to live according to their values and the values of the winners in the Great Patriotic War, instead of being guided by values that extoll Roman Shukhevich, Stepan Bandera and other Petlyuras.

Olga Belova: You said we need to wait for the president-elect to take actual steps. Everyone realises that it is imperative to sit down and talk no matter what happens. What should Kiev’s first actions, statements and steps be so that, to use your words, Moscow “gives them another chance” to a peaceful resolution of the situation?

Sergey Lavrov: Most importantly, the new or old government should be able to talk and reach agreements and to respect international law and Ukraine’s international obligations. Such obligations include an international legal instrument which is the UN Security Council resolution, which approved the Minsk Agreements. A direct dialogue between Kiev, on the one hand, and Donetsk and Lugansk, on the other hand, lies at the core of these agreements. This will be the key to success. To reiterate, we heard about the plans to continue the settlement in the election statements, in particular, on the part of Mr Zelensky and his staff, but this time with the involvement of the United States and Great Britain and without direct dialogue with the proclaimed republics − DPR and LPR.

When contenders for a post make such statements, they will then be somehow tied in with such a position in the future. I hope that life will make them realise that there’s no alternative to implementing the Minsk Agreements and, in any case, that there’s no alternative to direct dialogue with the people who represent an enormous part of your nation, if you still consider them to be such, of course.

Olga Belova: We see that so far no one has been talking to them, and there’s no direct dialogue with the republics. Recently, the DPR published the foreign policy concept which shows a certain dualism: on the one hand, there’s a commitment to the Minsk Agreements and, on the other hand, the Republic of Donbass recognises itself as an independent state. What does Moscow think about the dualism of this document? What is your vision of the future of that region following the elections?

Sergey Lavrov: I don’t see anything unusual here, because these republics proclaimed sovereignty five years ago, in May 2014, responding to what we just talked about, namely, radical nationalists who came out with strong anti-Russian statements and launched an attack on the language, cultural and religious rights of ethnic minorities. It started a long time ago. These republics responded by declaring independence. Let’s remind our Western colleagues, if they ever take any interest in these unpleasant facts from recent history, that these republics did not attack the rest of Ukraine. The rest of Ukraine declared them terrorists. This, of course, is a stunning phenomenon in modern diplomacy and politics.

The rest of Ukraine was represented by the putschists who seized power in Kiev and launched an attack on millions of their fellow citizens demanding that they submit to illegal authorities. So, as I understand it, independence was simply reaffirmed in these doctrinal documents adopted in Donbass. But after this independence was declared five years ago in May − returning to what we think about the then elections and the election of Poroshenko solely because he proclaimed that his goal was immediate peace and an immediate agreement on resolving the Donbass problem by way of talks, Russia talked these republics into agreeing to a political process.

Political and diplomatic efforts were interrupted by the military actions of Kiev, which did not respect the truce and ceasefire agreement. There was the August offensive which ended badly for the Ukrainian armed forces and, most importantly, claimed a huge number of human lives, followed by the January offensive in Debaltsevo. Only after receiving a rebuff, did Petr Poroshenko sit down at the negotiating table. That’s how the Minsk Agreements were signed.

I was in Minsk and saw how the leaders of the four countries spent 17 hours at the negotiating table taking short breaks, mostly talking between themselves, and sometimes inviting us as experts to clarify certain fine points. It took considerable effort to convince the leaders of the DPR and LPR who were present in Minsk to give the go-ahead to the Minsk Agreements. We did it. We convinced them to once again demonstrate their willingness, even determination, if you will, to achieve peace with the rest of Ukraine.

Unfortunately, the way the current Ukrainian authorities see our efforts is disappointing. Despite provocations, we will push for these agreements to be implemented. We are a country that is capable of reaching agreements.

Olga Belova: That is, if I understood you correctly, Moscow is still capable and willing to continue to influence the leadership of these republics? Are we going to push them to sit down and talk as best we can, or not? I’m asking this because the leaders of the republics have made it clear that they have parted ways with Kiev.

Sergey Lavrov: You said there was a dual decision to reaffirm independence and commitment to the Minsk Agreements. To a certain extent (I will not frame it in terms of a percentage), this is the result of our influence on them and our call for them not to follow the example of the Ukrainian authorities which break down and trample upon their own promises. We will continue to exert this influence. We have long been calling, above all, the Germans and the French, to realise their responsibility for Kiev’s behaviour, because the Minsk Agreements involve, above all, proactive steps on the part of the Ukrainian authorities. The Contact Group is the only format where Donetsk, Lugansk and Kiev sit down at one table with the representatives of the OSCE and Russia. It took an inordinate amount of effort to create it, primarily because Mr Poroshenko began to back pedal shortly after the Minsk Agreements had been signed, and refused to maintain direct dialogue with the republics. But we forced our Ukrainian colleagues do that. Although in practical work − the Contact Group meets every month − and even more often than that the Ukrainian government outwardly sabotages everything that was agreed upon, be it security, separating forces and means, the political process, coordinating the formula for conducting elections or providing this region with a special status in accordance with the Minsk Agreements. There is an open and blatant sabotage. We need to understand how the election results will affect the Ukrainian delegation’s activities in the Contact Group, and what kind of people will be delegated there.

Olga Belova: Indeed, now everything depends on how the presidential election will end, including the situation in the Kerch Strait, which was endlessly brought up in the first part of the campaign, before the first round. How harshly are we ready to respond if another provocation is made, especially considering that NATO has declared its readiness to support Ukrainian warships if they undertake another breakthrough?

Sergey Lavrov: Morally and politically – maybe they will support it. But I do not see a situation where NATO ships will join these adventurers for a military provocation. I do not foresee such a situation, and, considering the information that we have, I have reason to believe that this has already been decided at NATO.

Olga Belova: So all the support they will be getting is just words?

Sergey Lavrov: Probably, as it was the last time, a condemnation, and once again they will come up with some new sanctions. As we have said many times, we have no problem with Ukrainian warships passing from the Black Sea to their ports in the Sea of Azov. The only condition is to comply with the safety requirement for navigation along the Kerch Strait. It is a complex stretch of water, which is quite shallow and doesn’t go in a straight line and requires compulsory pilotage as well as coordination when it comes to the weather conditions. All ships — and there are thousands of them — stop at the entrance to the Kerch Strait, report to the channel operators, pilotage, recommendations, and, depending on the weather forecast, move on to the Sea of Azov, as was done before Ukraine’s warships last November. They passed smoothly without any incidents.

In November 2018, Petr Poroshenko, obviously during the election heat, tried to create a scandal to have reason to appeal to the West again, complaining of Russia harassing him, and insisting on more sanctions. He is better at it than many others. So the warships tried to secretly pass through the Kerch Strait, trespassing into our territorial waters – the part that was Russia's territorial waters even before the referendum in Crimea. What they did actually boiled down to probing the limits of those who ensure the security of the Kerch Strait and the territorial integrity of the Russian Federation.

I must note that among the numerous arguments our opponents seem to forget is the fact that the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea actually implies a so-called unimpeded passage through the territorial waters of a foreign state, including military vessels, subject to several conditions. One of them is the mandatory fulfillment of security requirements, which in this case was grossly violated. The second is that a coastal state cannot allow military ships to maneuver through its territorial waters. That is, you either pass complying with the rules or you violate the Convention. What they did was military maneuvers, trying to hide from our border guards. This much is clear to all without exception. I have no doubt about it.

That we have nothing to hide can be confirmed by a very simple fact.

In mid-December, German Chancellor Angela Merkel asked President of the Russian Federation Vladimir Putin to allow German specialists to observe the process to better understand what the hitch was and to study the conditions for passing through the Kerch Strait. Vladimir Putin immediately agreed. We reaffirmed the agreement and asked for their names and dates that would suit them. They made a pause, and then suddenly my colleague, German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas, said at a meeting in January when I reminded him of this that they wanted to bring French experts along.

I said that was new, but I was confident that our President would also agree to French specialists being on this study tour. But after some time, the Germans sent us the concept of their visit, which was not a single visit at all but involved establishing a kind of permanent observation mission, which would be associated with the OSCE mission in Donbass, and would also include Ukrainians. All of them would be staying in our territory doing I do not know what.

Olga Belova: You mean they actually wanted to come and stay there?

Sergey Lavrov: Yes, they certainly wanted to stay. The Germans are usually very punctual and precise people. When Angela Merkel asked Vladimir Putin whether their experts could come and see, he said yes... Apparently, after that, they consulted with their big brothers.

Olga Belova: So they just thought it would be a good reason to enter and station their ships there?

Sergey Lavrov: Of course, but this is an absolutely hopeless story. At the same time, I can assure with all responsibility that if the Germans and the French still have an interest in visiting and seeing it firsthand, so as not to rely on the gossip that the Ukrainian side spreads, they are very welcome.

Olga Belova: You believe that Russia will not directly clash with NATO ships in the Kerch Strait because NATO will not have the courage to sail there.

But there is another place where Russian interests clash with those of its Western partners, which is Venezuela. Will Washington decide to stage a military intervention there? What do you think of this? If yes, how far is Russia ready to go in this region? Are we prepared for a direct and tough stand-off in the region that would culminate in a peace enforcement operation against those who don’t want this, provided that all legal formalities are complied with?

Sergey Lavrov: I don’t want to bring up this scenario. I am convinced that Washington does not yet completely understand that its line regarding Venezuela has become deadlocked. They believed that the people of Venezuela would rebel against the incumbent government from the very outset, that they would be disappointed with the government’s inability to ensure the normal operation of the socioeconomic sector. Our Western colleagues took care of this: The United States froze the Venezuelan oil company’s accounts, and the United Kingdom impounded the country’s gold reserves. They hoped to stifle Venezuela using economic methods. When the crisis was in its early stage, they also organised humanitarian relief aid deliveries and tried to cross the Venezuelan border. Obviously, that was a very cheap show. Yes, they said all the options were on the table, but they obviously expected a blitzkrieg. However, they admit that no blitzkrieg took place. Indeed, the country faces a very complicated economic situation which was complicated and continued to deteriorate even before all this began. We repeatedly advised the government of Venezuela, at its request, how to launch economic reforms. Quite possibly, someone did not like this, and they also decided to halt this process, so as to prevent the situation from working in favour of the Maduro government. They decided to further stifle Venezuela by economic and financial methods. When the blitzkrieg petered out, when it became clear that the people of Venezuela had their own pride and a feeling of national dignity, when they became obviously insulted by a situation when, speaking from abroad, US Vice President Mike Pence noted that he was appointing Juan Guaido as Acting President, one should be very far from historical experience while hoping that the people of Venezuela would “swallow” this.

Today, when the Americans continue to say that all options are on the table, I don’t doubt the fact that they are assessing the consequences of an audacious military undertaking. It is highly unlikely that anyone in Latin America will support them. To the best of my knowledge, they are counting on one or two countries. I have no doubts, and I know that the Latin Americans have a great feeling of personal dignity. This would pose a challenge to all of them, all the more so as a righteous rejection of such a dictate has been accumulating for several months already, especially when the Americans de-mothballed the Monroe Doctrine and said it was quite appropriate to use this doctrine in the current situation.

On April 17, US National Security Adviser John Bolton said the United States was bringing its own version of freedom to the region. And what version of freedom does the region prefer? Would you like to ask them how they perceive their own freedom?

I hope very much that a line which stipulates talks and which is conducted by Mexico, Bolivia, Uruguay and the Caribbean Community will prevail. President of Venezuela Nicolas Maduro is ready for such talks, and he has repeatedly confirmed this in public. Juan Guaido emphatically and ostentatiously refuses, comprehending Washington’s support and counting on this support alone. It appears that he has copied the bad example of President of Ukraine Petr Poroshenko who also behaved in the same way with regard to the need for conducting a national dialogue that would involve all political forces, and he hoped that Washington would shield him whatever the situation.

Olga Belova: Washington says it is bringing freedom to the region. But what is it that we are bringing to the region?

Sergey Lavrov: We want international law to be respected in the region as well as in the world at large. This means that states build their relations via dialogue and a balance of interests takes shape. This also means that we listen to each other and want to negotiate mutually beneficial security, economic and humanitarian projects as well as projects in any other spheres, where countries and peoples operate. Our relations with the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) rest precisely on this basis. We are finalising talks with the South American Common Market (MERCOSUR). There is an agreement with the Central American Integration System (CAIS) and a number of other sub-regional organisations.

We have even-handed and good relations with practically all the Latin American countries. We don’t force anyone to do things we would like to get as unilateral advantages. The entire US policy towards Russia comes down to the US ambassador in any country visiting, with envious regularity, government agencies and demanding that they don’t receive Russian delegations, nor send delegations to Russia, nor trade with Russia, nor buy anything from Russia, particularly military products, and the like.

You can’t conceal information in today’s world. We learn this the moment these “visits” occur, the more so that the Americans are not particularly hiding the fact. They publicly say: Don’t communicate with Russia. It is Russia along with Iran and Cuba that are to blame for what is going on in Venezuela. They demand that not a single Russian soldier be found in Venezuela because the US wants it this way: no one located outside of the Western Hemisphere has the right to be there at all. Our explanation that the Russian military are performing contractual obligations servicing military equipment that was supplied on fully legitimate terms way back in the 2000s are simply disregarded. The fact that the US military and other NATO personnel – Britons and Canadians – have filled Ukraine is not mentioned. It looks like they proceed from logic suggested by the saying “What is allowed to Jupiter, is not allowed to the bull.” This is rotten logic, very much so, and it will not help our US colleagues. I am quite hopeful that they will come to understand this. Yes, within some historically very brief period preceding the next electoral cycles in the US, they are likely to reap certain benefits because they are brazenly putting pressure on countries that are unable to resist them. But in the long term, increasingly more countries will proceed from the assumption that America is just an unreliable and impolite partner that is abusing its influence in the world. The UN Charter insists on sovereign equality of states. We build our relations precisely in this way.

I cannot refrain from mentioning the fact that the United States has recently added a frontal attack on Orthodox Christianity to the arsenal of its policy towards Russia. Given that the Russian Orthodox Church was a world Orthodoxy leader, the crazy gamble involving the conferral of autocephality on the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, known today as the Orthodox Church of Ukraine, a gamble undertaken by the Istanbul Patriarch Bartholomew, has been – we have enough facts to claim this – inspired and supported by Washington. Today Washington is engaged in tough diplomatic action as it works with other Orthodox Churches that have refused to support the Istanbul Patriarch’s self-willed decision. Its aim is to somehow make them recognise what has happened. This unceremonious and gross interference in church affairs is at odds with all diplomatic norms and international law in general. And this is deplorable.

We would like the United States to be a decent member of the world community. We are open to dialogue but their approach to relations is highly utilitarian and selfish.

They suggest that we and the Chinese cooperate with them when it comes to Afghanistan and North Korea because they are unable to operate successfully on their own there. And we accept this because a settlement in Afghanistan, on the Korean Peninsula and in Syria, on which we can communicate usefully, is also in our interests. We don’t dig in our heels and say that we will not negotiate on these issues if they don’t want to discuss other ones. Our position is more pragmatic. Russia is ready to work with all influential parties who see eye to eye with us and can help to achieve a settlement.

But generally their policy towards Russia is based solely on the wish to make us accept their unilateral domination and renounce international law. This is deplorable and cannot last ad infinitum. The Americans will be unable to sustain this course for long. They are antagonising a huge number of countries. So, it is in their best interests to come back to square one and start talking to all countries respectfully. Currently, they are doing this arrogantly, something that cannot help their interests.

Olga Belova: We do need to talk, but so far talking to these Western partners of ours has been quite challenging. There is a saying: Those who do not want to talk with Sergey Lavrov will have to deal with Sergey Shoigu. This echoes what you have been saying. In your opinion, who is the main guardian of peace now, the military or the diplomats? What enables Russia to maintain parity: state-of-the-art armaments or the power of words? Who has priority at present?

Sergey Lavrov: When the Soviet Union was being dissolved, pro-democracy forces both here in Russia and in the West were ecstatic. There was a theory whereby the factor of strength in international relations was no longer relevant now that the bipolar world order was no more, the Cold War became a thing of the past, ideological differences faded away and we all came together on a strong democratic footing. This euphoric state persisted for several years. The situation was far from rosy of course, but as you may remember, in the 1990s Russia was young and proactive in its commitment to working with the US and NATO, all but deciding to join the alliance. However, disillusionment came very quickly. It dawned on everyone that behind the veil of these beautiful words the West meant only one thing: Russia was to give up on using the factor of strength in its policy, while the West would continue relying on it. Why was NATO still around after the Warsaw Pact was dissolved? How come we did not come together within the OSCE to transform it into a pan-European, Euro-Atlantic organisation without any western or eastern variants in order to address all questions without exception based on consensus? It did not happen. Of course, the plan they nurtured was to use Russia’s weakness in the first years after the collapse of the Soviet Union in order to achieve an overwhelming military and strategic advantage.

President of Russia Vladimir Putin has talked about this on numerous occasions. It became clear to us that our positive attitude towards the West was not reciprocal. The West continued to push NATO further east in violation of all possible promises, moving its military infrastructure to our borders, and there was no end in sight, especially when the US withdrew from the ABM Treaty. At this point, everything was clear. Decisions were taken, paving the way to the development of the weapons the President presented during his address last year to the Federal Assembly. Of course, it is highly regrettable that in today’s world no one will talk to you, unless you have a strong army and cutting-edge weapons.

Olga Belova: Has it become easier to talk?

Sergey Lavrov: When I was appointed to this post, the situation was already beginning to change. However, I would not say that talking was a challenge before, and that now things are easier. Unfortunately, the US, as our main partner, labelled Russia its “high-priority adversary,” as you have said. Later the US backtracked, and propelled China to this position. Later Russia was again on the list, and after that we were accompanied by China and Iran. They want to set their policy straight. They want to be in total control, but have yet to understand how this can be done. Sanctions work in some cases, but definitely not with Russia. They will not work with other countries that respect their history and identity.

We have no problems talking with the Europeans when it comes to relations with each specific country. There are challenges in our dialogue with NATO, since the US decided to convene meetings of the Russia-NATO Council with the sole purpose of lecturing us on Ukraine and other matters or criticising us for allegedly violating and dismantling the Intermediate-Range and Shorter-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. We do not intend to attend any meetings of this kind in the future. If they want to have a serious conversation, they have to convene a Russia-NATO Council meeting at the military level. The outgoing Supreme Allied Commander Europe of NATO Allied Command Operations, General Curtis Scaparrotti, recently voiced regret over the lack of military-to-military interaction with Russia that existed even during the Cold War. Better late than never. Let us hope that his successor in this position is receptive to this advice. This is what we hope for.

We have a very good dialogue with each country of the European Union. Yes, we sometimes happen to disagree. We have problems with the Baltic countries, with Poland, but we are ready to talk about them. Especially because the Baltic states are our neighbours, and we have good trade and investment cooperation in business. There are also security issues, because NATO is pushing its units into Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia. It is too close to our borders. At the same time, NATO is moving away from implementing the understandings we reached following the initiative of President of Finland Sauli Niinisto concerning flight safety over the Baltic. We responded to it; our military proposed ideas that would help allay concerns. It is possible to talk with everyone. On a bilateral basis, even the Baltic countries show interest: President of Estonia Kersti Kaljulaid has visited Moscow. We are talking in a neighbourly way about what we can do so that people can live comfortably and there would be no security concerns. But the collective platforms – NATO and the EU – are dominated by mutual responsibility: the Russophobic minority in the EU imposed sanctions on Russia, punishing us for supporting the will of the people of Crimea. This position of the European Union is now extended every six months, and no one can do anything, although individually, they assure us that the majority already understands that this is a dead end and something needs to be done. We are patient people, but as long as the EU as an organisation is not ready to restore all the mechanisms of our strategic partnership – we used to have summits twice a year, a ministerial council that oversaw more than 20 sectoral dialogues, four common spaces ... All that was frozen because someone decided to try to “punish” us. Funny, honestly.

We are always open to honest, equal and respectful dialogue both through the military and through diplomatic channels. We have a very good tradition with a number of countries, in particular, with Italy and Japan, the 2 + 2 format, when Sergey Shoigu and I meet with our colleagues, the four of us. This is a very interesting format. It enables us to consider security issues through the prism of diplomacy and vice versa – purely military issues in foreign policy. We had such formats with the Americans and the British – but they froze them on their own initiative. But with the Italians and the Japanese, we continue these processes.

Olga Belova: I seem to understand why they froze them. Because when you two come to the negotiations, it’s simply impossible to resist you in such a duo.

Sergey Lavrov: Oh, don't say that. We are modest people. Modest and polite.

Olga Belova: You’re modest and polite – but are you ready to give everyone a second chance, as with Ukraine?

The Trump administration once again has graphically demonstrated that in the young, turbulent 21st century, “international law” and “national sovereignty” already belong to the Realm of the Walking Dead.

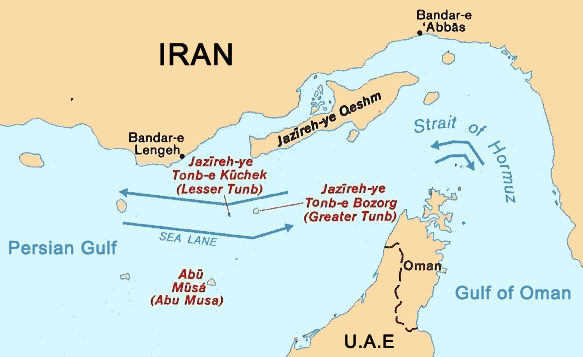

The Trump administration once again has graphically demonstrated that in the young, turbulent 21st century, “international law” and “national sovereignty” already belong to the Realm of the Walking Dead. In tandem, IRGC Navy Commander Rear Admiral Alireza Tangsiri has evoked the unthinkable in terms of what might develop out of the U.S. total embargo on Iran oil exports; Tehran could block the Strait of Hormuz.

In tandem, IRGC Navy Commander Rear Admiral Alireza Tangsiri has evoked the unthinkable in terms of what might develop out of the U.S. total embargo on Iran oil exports; Tehran could block the Strait of Hormuz.