Although defense budgets had actually increased in the post-Vietnam 1970s, for example, veterans of the era still shared horror stories about the “hollow” military in the years following the final withdrawal from Saigon. That cloud had lifted soon enough, thanks to sustained efforts — via the medium of suitably adjusted intelligence assessments — to portray the Soviet Union as the Red Menace, armed and ready to conquer the Free World.

On the other hand, the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union had posed a truly existential threat. The gift that had kept on giving, reliably generating bomber gaps, missile gaps, civil-defense gaps, and whatever else was needed at the mere threat of a budget cut, disappeared almost overnight. The Warsaw Pact, the U.S.S.R.’s answer to NATO, vanished into the ash can of history. Thoughtful commentators ruminated about a post–Cold War partnership between Russia and the United States.

American bases in Germany emptied out as Army divisions and Air Force squadrons came home and were disbanded. In a 1990 speech, Senator Sam Nunn of Georgia, revered in those days as a cerebral disperser of military largesse, raised the specter of further cuts, warning that there was a “threat blank” in the defense budget and that the Pentagon’s strategic assessments were “rooted in the past.” An enemy had to be found.

For the defense industry, this was a matter of urgency. By the early 1990s, research and procurement contracts had fallen to about half what they’d been in the previous decade. Part of the industry’s response was to circle the wagons, reorganize, and prepare for better days. In 1993, William Perry, installed as deputy defense secretary in the Clinton Administration, summoned a group of industry titans to an event that came to be known as the Last Supper. At this meeting he informed them that ongoing budget cuts mandated drastic consolidation and that some of them would shortly be out of business.

Perry’s warning sparked a feeding frenzy of mergers and takeovers, lubricated by generous subsidies at taxpayer expense in the form of Pentagon reimbursements for “restructuring costs.” Thus Northrop bought Grumman, Raytheon bought E-Systems, Boeing bought Rockwell’s defense division, and the Lockheed Corporation bought the jet-fighter division of General Dynamics. In 1995 came the biggest and most consequential deal of all, in which Martin-Marietta merged with Lockheed.

The resultant Lockheed Martin Corporation, the largest arms company on earth, was run by former Martin-Marietta CEO Norman R. Augustine, by far the most cunning and prescient executive in the business. Wired deeply into Washington, Augustine had helped Perry craft the restructuring subsidies for companies like his own — essentially, a multibillion-dollar tranche of corporate welfare. In a 1994 interview, he shrewdly predicted that U.S. defense spending would recover in 1997 (he was off by only a year). In the meantime, he would scour the world for new markets.

In this task, Augustine could be assured of his government’s support, since he was a member of the little-known Defense Policy Advisory Committee on Trade, chartered to provide guidance to the secretary of defense on arms-export policies. One especially promising market was among the former members of the defunct Warsaw Pact. Were they to join NATO, they would be natural customers for products such as the F-16 fighter that Lockheed had inherited from General Dynamics.

There was one minor impediment: the Bush Administration had already promised Moscow that NATO would not move east, a pledge that was part of the settlement ending the Cold War. Between 1989 and 1991, the United States and the Soviet Union had amicably agreed to cut strategic nuclear forces by roughly a third and to withdraw almost all tactical nuclear weapons from Europe.

Meanwhile, the Soviets had good reason to believe that if they pulled their forces out of Eastern Europe, NATO would not fill the military vacuum left by the Red Army. Secretary of State James Baker had unequivocally spelled out Washington’s end of that bargain in a private conversation with Mikhail Gorbachev in February 1990, pledging that NATO forces would not move “one inch to the east,” provided the Soviets agreed to NATO membership for a unified Germany.

The Russians certainly thought they had a deal. Sergey Ivanov, later one of Vladimir Putin’s defense ministers, was in 1991 a KGB officer operating in Europe. “We were told . . . that NATO would not expand its military structures in the direction of the Soviet Union,” he later recalled. When things turned out otherwise, Gorbachev remarked angrily that “one cannot depend on American politicians.” Some years later, in 2007, in an angry speech to Western leaders, Putin asked: “What happened to the assurances our Western partners made after the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact? Where are those declarations today? No one even remembers them.”

Even at the beginning, not everyone in the administration was intent on honoring this promise. Robert Gates noted in his memoirs that Dick Cheney, then the defense secretary, took a more opportunistic tack: “When the Soviet Union was collapsing in late 1991, Dick wanted to see the dismantlement not only of the Soviet Union and the Russian empire but of Russia itself, so it could never again be a threat to the rest of the world.” Still, as the red flag over the Kremlin came down for the last time on Christmas Day, President George H. W. Bush spoke graciously of “a victory for democracy and freedom” and commended departing Soviet leader Gorbachev.

But domestic politics inevitably dictate foreign policy, and Bush was soon running for reelection. The collapse of the country’s longtime enemy was therefore recast as a military victory, a vindication of past imperial adventures. “By the grace of God, America won the Cold War,” Bush told a cheering Congress in his 1992 State of the Union address, “and I think of those who won it, in places like Korea and Vietnam. And some of them didn’t come back. Back then they were heroes, but this year they were victors.”

This sort of talk was more to the taste of Cold Warriors who had suddenly found themselves without a cause. The original neocons, though reliably devoted to the cause of Israel, had a related agenda that they pursued with equal diligence. Fervent anti-Communists, they had joined forces with the military-industrial complex in the 1970s under the guidance of Paul Nitze, principal author in 1950 of the Cold War playbook — National Security Council Report 68 — and for decades an ardent proponent of lavish Pentagon budgets.

As his former son-in-law and aide, W. Scott Thompson, explained to me, Nitze fostered this potent union of the Israel and defense lobbies through the Committee on the Present Danger, an influential group that in the 1970s crusaded against détente and defense cutbacks, and for unstinting aid to Israel. The initiative was so successful that by 1982 the head of the Anti-Defamation League was equating criticism of defense spending with anti-Semitism.

By the 1990s, the neocon torch had passed to a new generation that thumped the same tub, even though the Red Menace had vanished into history. “Having defeated the evil empire, the United States enjoys strategic and ideological predominance,” wrote William Kristol and Robert Kagan in 1996. “The first objective of U.S. foreign policy should be to preserve and enhance that predominance.”

Achieving this happy aim, calculated these two sons of neocon founding fathers, required an extra $60–$80 billion a year for the defense budget, not to mention a missile-defense system, which could be had for upward of $10 billion. Among other priorities, they agreed, it was important that “NATO remains strong, active, cohesive, and under decisive American leadership.”

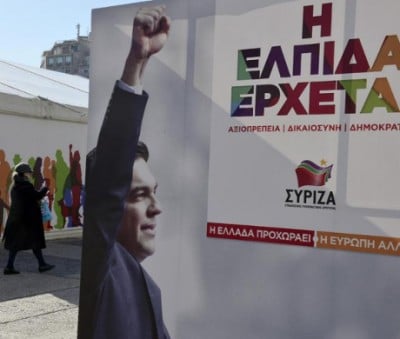

As it happened, NATO was indeed active, under Bill Clinton’s leadership, and moving decisively to expand eastward, whatever prior Republican understandings there might have been with the Russians. The drive was mounted on several fronts. Already plushly installed in Warsaw and other Eastern European capitals were emissaries of the defense contractors. “Lockheed began looking at Poland right after the Wall came down,” Dick Pawloski, for years a Lockheed salesman active in Eastern Europe, told me. “There were contractors flooding through all those countries.”

Meanwhile, a coterie of foreign-policy intellectuals on the payroll of the RAND Corporation, a think tank historically reliant on military contracts, had begun advancing the artful argument that expanding NATO eastward was actually a way of securing peace in Europe, and was in no way directed against Russia.

Chief among these pundits was the late Ron Asmus, who subsequently recalled a RAND workshop held in Warsaw, just months after the Wall fell, at which he and Dan Fried, a foreign-service officer deemed by colleagues to be “hard line” toward the Russians, and Eric Edelman, later a national-security adviser to Vice President Cheney, discussed the possibility of stationing American forces on Polish soil.

Eminent authorities weighed in with the reasonable objection that this would not go down well with the Russians, a view later succinctly summarized by George F. Kennan, the venerated architect of the “containment” strategy:

Expanding NATO would be the most fateful error of American policy in the post cold-war era. Such a decision may be expected to inflame the nationalistic, anti-Western and militaristic tendencies in Russian opinion; to have an adverse effect on the development of Russian democracy; to restore the atmosphere of the cold war to East-West relations, and to impel Russian foreign policy in directions decidedly not to our liking.

In retrospect, Kennan seems as prescient as Norm Augustine, but it didn’t make any difference at the time. When he wrote that warning, in 1997, NATO expansion was already well under way, and with the aid of a powerful supporter in the White House. “This mythology that it was all neocons in the Bush Administration, it’s nonsense,” says a former senior official on both the Clinton and Bush National Security Council staffs who requested anonymity. “It was Clinton, with the help of a lot of Republicans.”

This official credits the persuasive powers of Lech Walesa and Václav Havel at a 1994 summit meeting with Clinton’s conversion to the cause of NATO expansion. Others point to a more urgent motivation. “It was widely understood in the White House that [influential foreign-policy adviser Zbigniew] Brzezinski told Clinton he would lose the Polish vote in the ’96 election if he didn’t let Poland into NATO,” a former Clinton White House official, who requested anonymity, assured me.

To an ear as finely tuned to electoral minutiae as the forty-second president’s, such a warning would have been incentive enough, since Polish Americans constituted a significant voting bloc in the Midwest. It was no coincidence then that Clinton chose Detroit for his announcement, two weeks before the 1996 election, that NATO would admit the first of its new members by 1999 (meaning Poland, the Czech Republic, and Hungary).

He also made it clear that NATO would not stop there. “It must reach out to all the new democracies in Central Europe,” he continued, “the Baltics and the new independent states of the former Soviet Union.” None of this, Clinton stressed, should alarm the Russians: “NATO will promote greater stability in Europe, and Russia will be among the beneficiaries.” Not everyone saw things that way; in Moscow there was talk of meeting NATO expansion “with rockets.”

Chas Freeman, the assistant secretary of defense for international security affairs from 1993 to 1994, recalls that the policy was driven by “triumphalist Cold Warriors” whose attitude was, “The Russians are down, let’s give them another kick.” Freeman had floated an alternate approach, Partnership for Peace, that would avoid antagonizing Moscow, but, as he recalls, it “got overrun in ’96 by the overwhelming temptation to enlist the Polish vote in Milwaukee.”

In April 1997, Augustine took a tour of his prospective Polish, Czech, and Hungarian customers, stopping by Romania and Slovenia as well, and affirmed that there was great potential for selling F-16s. Clinton had spoken of NATO being as big a boon for Eastern Europe as the Marshall Plan had been for Western Europe after the Second World War, and many of the impoverished ex-Communist countries, some with small and ramshackle militaries, were eager to get on the bandwagon.

“Augustine would look them in the eye,” recalls Pawloski, the former Lockheed salesman, “and say, ‘You may have only a small air force of twenty planes, but these planes will have to play with the first team.’ Meaning that they’d be flying with the U.S. Air Force and they would need F-16s to keep up.” Actually, Augustine had rather more going for him than this simple sales pitch, including a lavish dinner for Hungarian politicians he threw at the Budapest opera house.

Meanwhile, back in Washington, a new and formidable lobbying group had come on the scene: the U.S. Committee to Expand NATO. Its cofounder and president, Bruce P. Jackson, was a former Army intelligence officer and Reagan-era Pentagon official who had dedicated himself to the pursuit of a “Europe whole, free and at peace.” His efforts on the committee were unpaid. Fortunately, he had kept his day job — working for Augustine as vice president for strategy and planning at the Lockheed Martin Corporation.

Jackson’s committee stretched ideologically from Paul Wolfowitz and Richard Perle (known as the neocon “Prince of Darkness”) to Greg Craig, director of Bill Clinton’s impeachment defense and later Barack Obama’s White House counsel. Others on the roster included Ron Asmus, Richard Holbrooke, and Stephen Hadley, who subsequently became George W. Bush’s national-security adviser.

When I reached Jackson recently at his residence in Bordeaux, he reiterated what he had always said at the time: his efforts to expand NATO were undertaken independently of his employer. He suggested that they had even imperiled his job. “I would not say that senior executives supported my specific projects,” Jackson said.

“They thought I should be free to do what I wanted politically, provided I did not associate [Lockheed] with my personal causes. In short, they did nothing to stop me, and suggested to other employees to leave me alone so long as I did not drag LMC into politics or foreign policy. I finally left because I enjoyed my nonprofit work more than my day job.”

In this atmosphere of disinterested public service, Jackson and his friends devoted their evenings to cultivating support for congressional approval of Polish, Czech, and Hungarian membership in NATO, followed by further expansion. The setting for these efforts was a large Washington mansion not far from the British Embassy and the vice-presidential residence: the home of Julie Finley, a significant figure in Republican Party politics at that time who had, as she told me, “a deep interest in national security.”

A friend of hers, Nina Straight, describes Finley as someone who “knows how to be powerful and knows how to be useful.” As Finley relates, she noted in late 1996 that NATO expansion was facing opposition in Washington. “So I called Bruce Jackson and Stephen Hadley and Greg Craig and said, ‘Holy smokes, we have to get moving!’ ”

“We always met at Julie Finley’s house, which had an endless wine cellar,” Jackson reminisced happily. “Educating the Senate about NATO was our chief mission. We’d have four or five senators over every night, and we’d drink Julie’s wine while people like [Polish dissident] Adam Michnik told stories of their encounters with the secret police.”

[...]

In any event, the vision of Augustine and his peers that an enlarged NATO could be a fruitful market has become a reality. By 2014, the twelve new members had purchased close to $17 billion worth of American weapons, while this past October Romania celebrated the arrival of Eastern Europe’s first $134 million Lockheed Martin Aegis Ashore missile-defense system.

http://russia-insider.com/en/2015/01/19/2547