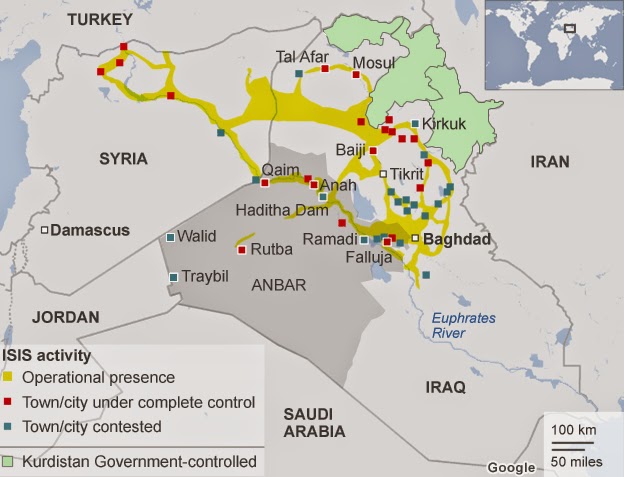

The United States President Barack Obama unveiled in a major speech on Wednesday his strategy to «degrade and ultimately destroy» the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria. The strategy has no timeline and, quintessentially, the US will pit Muslims against Muslims in a grim war through the deployment of ‘smart power’, which would ensure that American casualties are avoided. From all appearance, it will also be a self-financing war funded by the petrodollar Gulf Arab states of the Middle East.

The strategy is built on three pillars – firstly, setting well-defined limits to the actual American intervention in military terms, secondly, resuscitating the ‘regime change’ agenda in Syria and, thirdly, dispensing with any mandate from the United Nations. In essence, it becomes a repackaged version of the crudely unilateralist US intervention in the Middle East by the George W. Bush administration.

Clearly, Obama delayed the unveiling of his strategy until the public opinion in the US ‘matured’. Opinion polls show a high degree of approval rating in America for renewed US military intervention in Iraq and Syria. The gruesome killing of two American journalists by the Islamic State has no doubt inflamed public anger. But the main factor is the fear that has been injected into the American mind through weeks and months of media campaign projecting that the Islamic State posed a direct threat to the US’s ‘homeland security’. The ploy indeed worked, as the opinion polls testify. Obama’s timing is perfect, as he deftly chose the eve of the 11th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks to unveil his strategy before the American public.

Curiously, however, with the ‘maturing’ of the public opinion successfully accomplished, Obama also took pains yesterday to scale down the fear psychosis in America by clarifying that the US has «not detected specific plotting against our [American] homeland» by the Islamic State although its leaders have «threatened America and our allies». Instead, he portrayed the Islamic State as posing threat to the «people of Iraq and Syria, and the broader Middle East – including American citizens, personnel and facilities».

Clearly, not only has a sense of proportions been introduced that calms agitated American public opinion even as the country embarks upon another virtually open-ended war abroad, but Obama has found a rationale for recruiting the US’ Middle Eastern allies in the forthcoming war. Obama’s message to the American people is simple: ‘No need of anxiety syndrome, get on with your life, let your commander-in-chief handle this.’

In return, Obama held out the assurance that the parameters of the US military intervention will be well-defined. There will be «a systematic campaign of airstrikes» at the IS targets even as Iraqi forces go on offense; US will hunt down IS terrorists and increase its support to the Iraqi and Kurdish forces fighting the IS, including providing training and intelligence and equipment; Pentagon will deploy an additional 475 military personnel in Iraq (bringing the total to nearly 1600). But, «American forces will not have a combat mission – we will not get dragged into another ground war in Iraq».

Obama underscored that the war ahead will be «different from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. It will not involve American combat troops fighting on foreign soil». Instead, as the US has been doing in Yemen and Somalia «for years», this war «will be waged through a steady, relentless effort to take out the ISIL wherever they exist, using our airpower and our support for partner forces on the ground».

Obama stated that the US military operations directed against will extend into Syrian territory. He spelt out the strategy toward Syria, which is focused on ramping up military assistance to the Syrian opposition. Obama appealed to the US Congress to make available to him additional «authorities and resources to train and equip these [Syrian] fighters». In essence, a big escalation of the US intervention in Syria is in the offing.

Obama bluntly rejected any notions of the US relying on the Syrian regime. He called it an illegitimate regime and also vowed to «solve Syria’s crisis once and for all». Simply put, the US will accelerate the push for regime change in Syria.

Quite obviously, Washington realizes that it can never extract a mandate from the UN Security Council to bring about a ‘regime change’ in Syria in contravention of international law and the UN Charter. Obama, therefore, took a de tour and will simply chair a meeting of the UN Security Council later this month in New York «to further mobilize the international community» around his Iraq-Syria strategy.

The US claims to have so far assembled a «core coalition» of eight North Atlantic Treaty Organization [NATO] member countries (plus Australia) to fight the new war in the Middle East. But Obama said there is need of a «broad coalition of partners». He disclosed that accordingly, Secretary of State John Kerry is travelling across the Muslim Middle East «to enlist partners in this fight, especially Arab nations who can help mobilize Sunni communities in Iraq and Syria». He chose his words carefully, hinting that the US proposes to accord selective roles for the Shi’ites and Sunnis in the campaign against the IS. The most disconcerting part, of course, is the implied intention to enlist an active role on the Syrian theatre for countries such as Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Qatar.

No doubt, the enlisting of the petrodollar states ensures that money is not going to be a problem for the US in waging this open-ended war.

The New Middle East

Nonetheless, will Obama’s strategy work? Clearly, Obama’s strategy a cost-effective one and largely self-financing and might, therefore, be sustainable over a period of time. To be sure, there isn’t going to be any dearth of resources – financial or material or human – for fighting this war, given the involvement of the petrodollar states that have been pushing for regime change in Syria.

The American public may not militate anytime soon against this war, either. The American strategic community – especially, the think tankers and the media – will also be largely supportive, since this war explicitly dovetails with Israeli interests. In fact, the US is reassembling the same old axis in the Middle East, comprising Israel and the Sunni Arab oligarchies of the Gulf region. At the same time, the US will not be accountable to the UN Security Council. It is a «coalition of the willing» that is fighting this war and internal dissent within that coalition is highly improbable, which in turn would ensure that Washington kept the command and control of this war.

However, imponderables lie ahead. First and foremost, it is hugely significant that Obama avoided holding out any categorical affirmation of the unity of Iraq. He is also delightfully vague about what his expectations are out of an «inclusive» government in Baghdad.

The point is, although Washington could engineer the replacement of Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, whether it still leads to Sunni reconciliation is far from clear as of now. This is important because the US strategy can work only if there is wholesome Iraqi Sunni mobilization against the IS. Or else, it may turn even uglier as sectarian strife continues to tear apart Iraq’s unity.

But then, on the other hand, this also involves the question of Shi’ite empowerment in Iraq. Suffice to say, the US needs to invent some magical formula that refines the concept of democratic principles allowing majority rule in Iraq. Put differently, this is also a war that involves nation-building in Iraq and the US’s record in such enterprises abroad has been very dismal, to put it mildly. This is one thing.

The most disconcerting part of this war is going to be its Syrian chapter. Perhaps, the US estimates that now that Syria’s stockpiles of chemical weapons have been destroyed, it is a safe bet to launch attacks on that country. Even assuming it is so, the Syrian opposition still remains a revolving door for extremist groups, as the saga of the Islamic State proves. The US has learnt nothing and still hopes to use extremist elements as instruments of regional policies.

Indeed, failure comes at a very heavy cost, as Iraq and Syria in their present form may well cease to exist at the end of it all. Of course, the really intriguing part is that such a denouement may well be the US’s geopolitical objective. In a recent interview with the New York Times, Obama himself put his finger on the unraveling of the Sykes-Picot agreement of 1916 as the core issue of the Middle Eastern politics.

Equally, Obama’s intention to recruit as allies «Arab nations who can help mobilize Sunni communities» virtually acknowledges the sectarian dimension to the conflicts in Iraq and Syria. Now, there is a complicated backdrop of regional politics playing out here, involving these every same Sunni Arab nations as key protagonists. Would Obama have some recipe to heal the regional tensions? He’s had nothing to say. Interestingly, not once did Obama refer to Iran, either.

Obama’s strategy completely bypasses the UN and, in reality, undermines the UN Charter. He failed to convincingly explain the raison d’etre of this particular variant of US military intervention in the Muslim world – unilateralist but ‘risk-free’ and low-cost – since the US’ homeland security is not even in any imminent or conceivable danger.

At the end of the day, the impression becomes unavoidable that the US continues to arrogate to itself the prerogative to violate the sovereignty and territorial integrity of nation states on the basis of its self-interests. Indeed, that this hydra-headed war is going to assume many varied shapes as times passes and long after Obama disappears into history books is virtually guaranteed.

Obama’s presidency has come full circle by reinventing the neocon dogmas it once professed to reject. On the pretext of fighting the IS, which the US and its allies created in the first instance, what is unfolding is a massive neocon project to remold the Muslim Middle East to suit the US’ geopolitical objectives. Call it by whatever name, it is an imperial war – albeit with a Nobel as commander-in-chief.

Melkulangara BHADRAKUMAR

Former career diplomat in the Indian Foreign Service. Devoted much of his 3-decade long career to the Pakistan, Afghanistan and Iran desks in the Ministry of External Affairs and in assignments on the territory of the former Soviet Union. After leaving the diplomatic service, took to writing and contribute to The Asia Times, The Hindu and Deccan Herald. Lives in New Delhi.

von John J. Mearsheimer*

von John J. Mearsheimer*